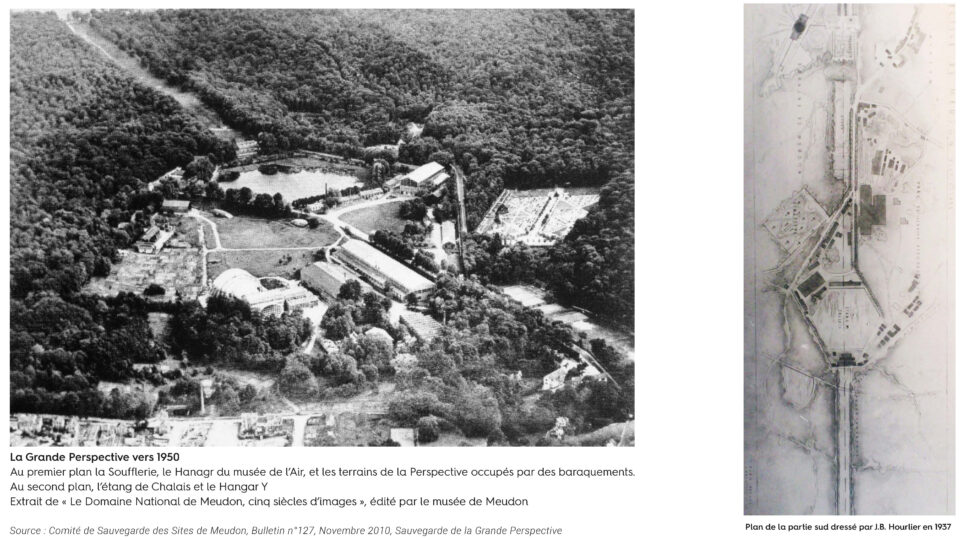

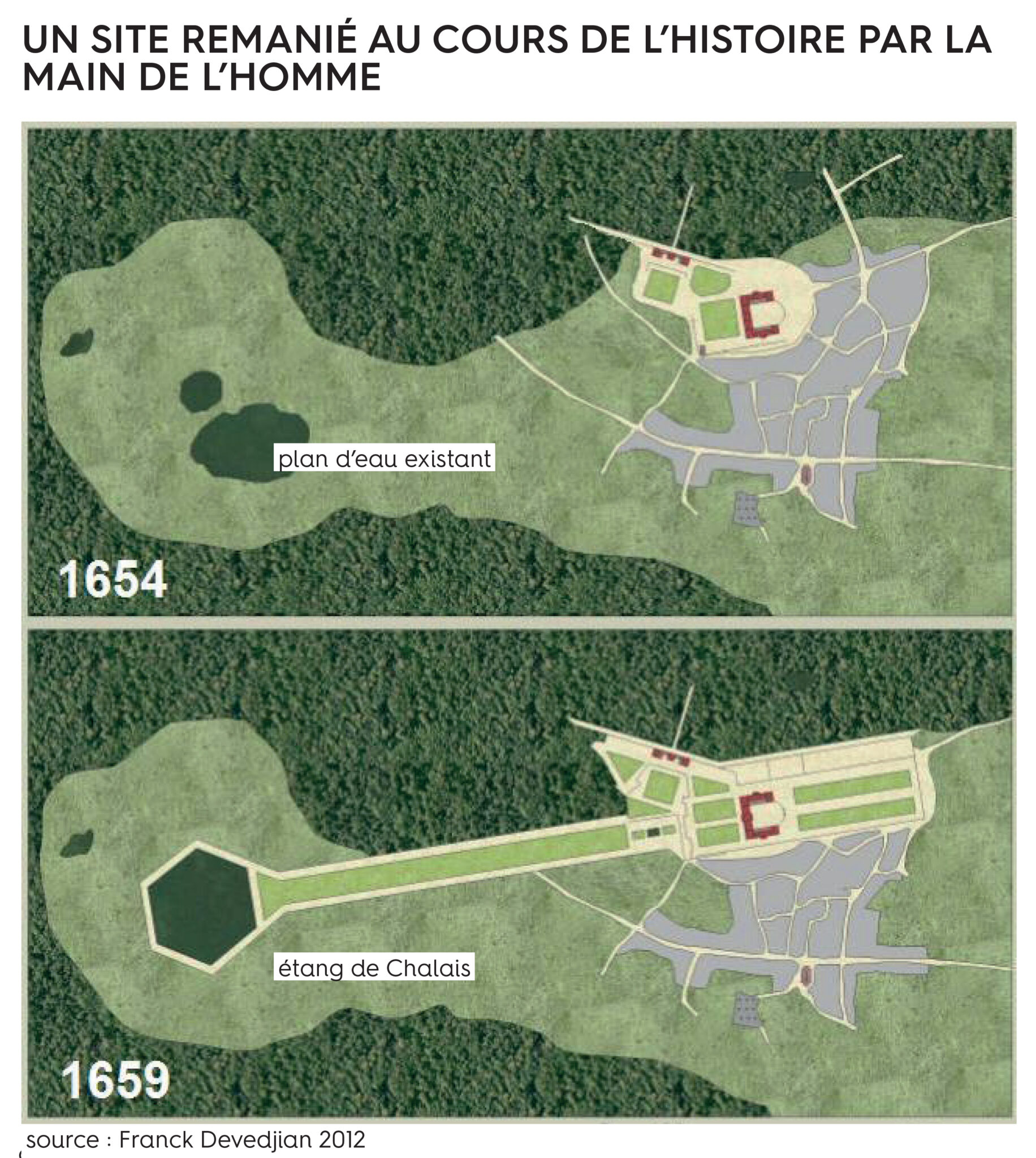

The most important landscaping work on the Meudon estate was carried out between 1654 and 1695.

The first period of work took place between 1654 and 1679, when Abel Servien, Superintendent of Finances, became owner of the estate. A second period continued between 1679 and 1695, when François Michel Le Tellier, Marquis de Louvois and minister to Louis XIV, succeeded him.

Louis Le Vau and André Le Nôtre are credited with the design of the axis, gardens and ponds of the Château de Meudon. These two landscape architects had already collaborated on the Château de Vault-Le-Vicomte.

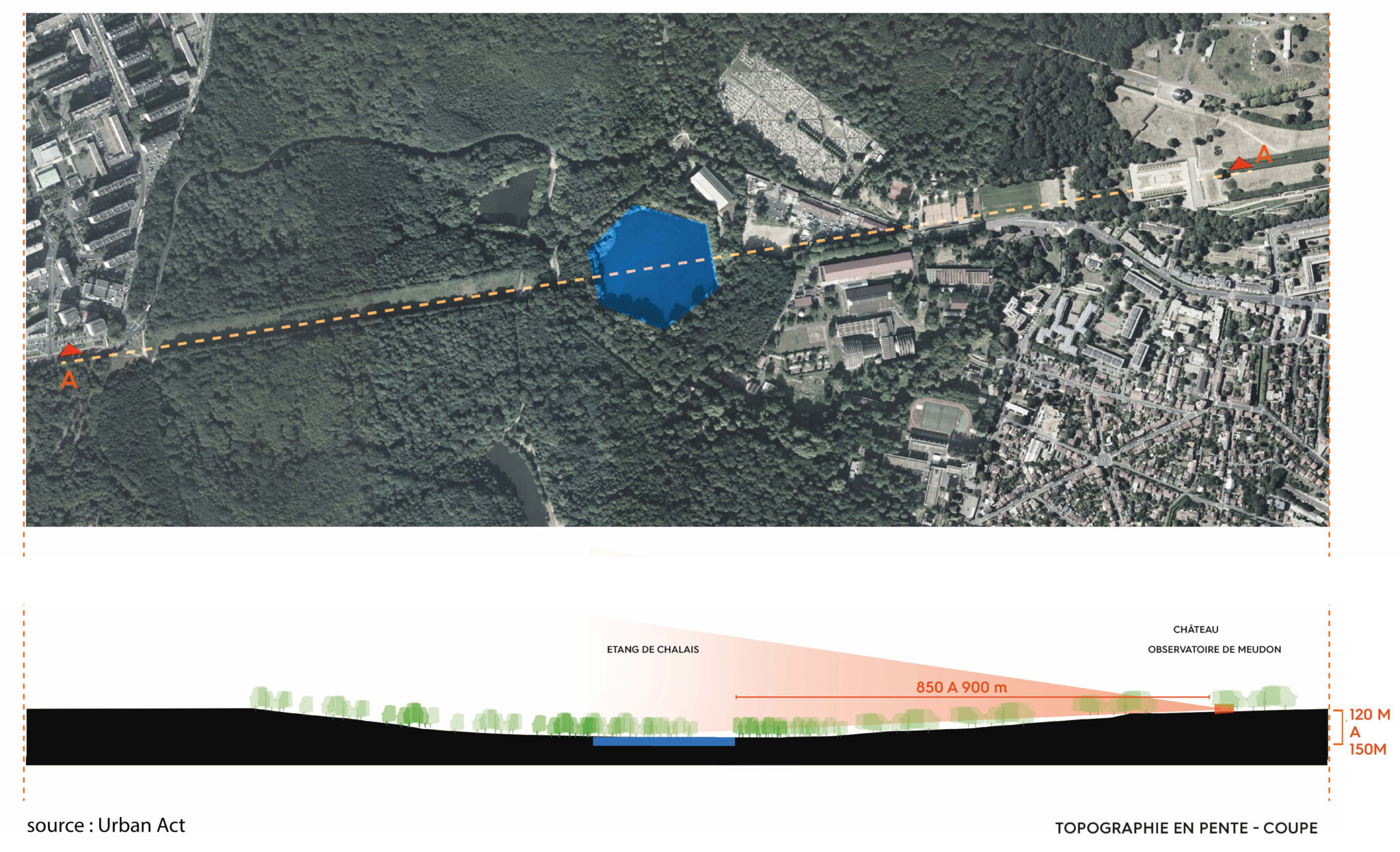

When Le Nôtre worked on the project around 1680, the axis projected from the observatory became an obvious link between town and forest. This grandiose perspective takes its cue from the singular geography of the site, positioning the hexagonal basin like a mirror in which the château can be reflected.

EPISODE 2: The undergrowth

Why this staircase? To cross this embankment. But where does this embankment come from?

From open meadow to young woodland: a new walk in the hollow of the slope

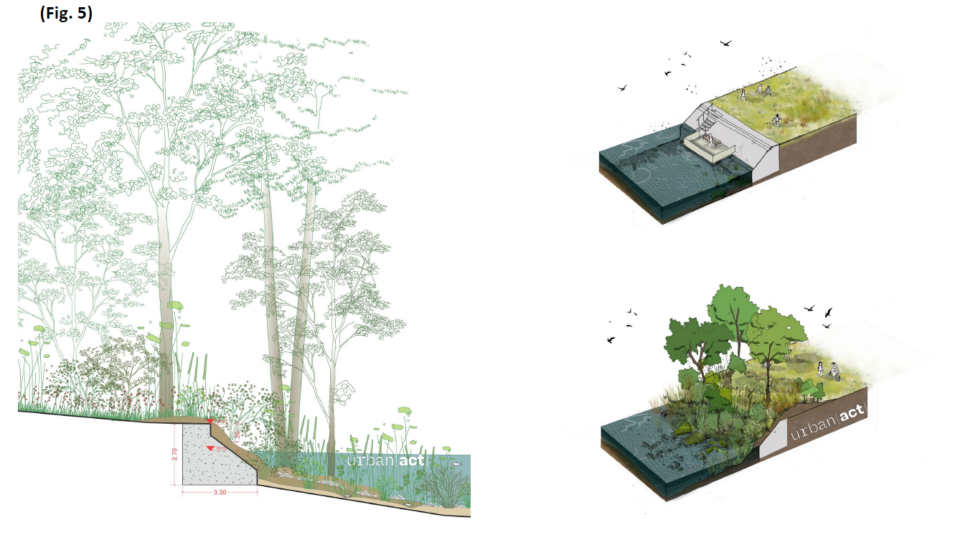

To create the Bassin de Chalais, Le Nôtre had to level the ground of the pre-existing meadow. The embankment was created by adding earth to level the ground. The meadow was at the same level as the walkway now glides between the trees.

The result of this vast earthwork is the pond, a superb horizontal mirror that captures the sky and clouds as it reflects the light. If you come early in the morning on a sunny day, you'll be amazed by the light that streams through the trees, giving the place a touch of mystery.

Designed to be imperceptible to the eye from the monumental axis, this embankment positions the pond overhanging the historic meadow, making the historic ground level more difficult to access. And while it was a trace of the site's origins, marking the boundary between field and meadow, it has gradually been abandoned.

Over the past fifty years or so, a woodland has developed here. The trees here are younger (locust, hornbeam, beech, etc.).

Recreating a walkway here, between the new trees and in the shade of the setback, provides a cool place to stroll. Close to the ground, at a depth of one meter, 13°C is guaranteed all year round, summer and winter alike.

EPISODE 3: Natural environments

An ecological, historical and cultural heritage

Although located on the edge of the natural zone of the forêt de Meudon, the park is completely disconnected from it by its perimeter wall.

A historical heritage survey revealed that there were no trees on the site when the axis was created. In place of today's woodland, a large, gently sloping meadow put the forest at a distance from the town. Traces of this meadow can be found as far back as 1930, before the site was gradually cleared. Today, the site has become a pioneer woodland, making it difficult to read the historical axis.

A landscape and ecological analysis revealed a collapse in biodiversity, caused by the site's isolation and neglect over the past 50 years.

To this end, an ecological heritage enhancement plan has been implemented to reconnect, breathe and open up existing environments. In particular, it is based on the conservation of old, mature woodlands and cavity trees, which are the most suitable for hosting a diverse range of fauna.

As the quality of the woodland on the site is very uneven (species, age, habit, alignment, density, phytosanitary condition, etc.), the landscape project has focused on reinforcing the different environments and the biological quality of the tree spaces through "strand by strand" management. In this way, a principle of fine selection has been put in place to assess and then prioritize trees according to their structural, ecological and historical qualities.

The woodlands were thinned out, giving priority to the development of the noblest species: ash, hornbeam and field maple. Trees that had grown along the riverbanks, having taken root on fragile soil, had to be felled. For all tree areas, invasive exotic species that had taken over the site in some places, such as ailantes, were systematically removed.

EPISODE 4: The waters

A hydraulic landscape in the heart of the forest: springs, streams, ponds and basins

Thanks to its marked geography, the Forêt de Meudon drains a large watershed. Water is everywhere in the forest: several ponds, with more or less rational geometries, punctuate the strolls of walkers (Fig.6). Underground springs continuously supply fountains such as Sainte-Marie (Fig. 7), to the east of the Chalais basin.

The creation of a hydraulic network integrated into the landscape to supply the water features is an ambitious, complex and crucial challenge. It was strongly inspired by the networks set up at Versailles to supply the fountains and fountains of the great gardens. Le Nôtre's heritage lies as much in his ingenious water management as in his landscape design.

Groundwater is sometimes present and feeds the ponds, while small brooks connect them to each other, such as the one that connects the Chalais pond (Fig. 8). The bed of this small stream has been repaired, and a small bridge created to allow access around the pond.

The two banks on either side of the creek have not been restored. They show the impact of vegetation on the stones and on this unique cultural heritage built by human hands. In the space of three centuries, the trees have taken root in the stones, almost completely destroying them.

EPISODE 5: The Chalais basin

Boundless geometry between architecture and landscape?

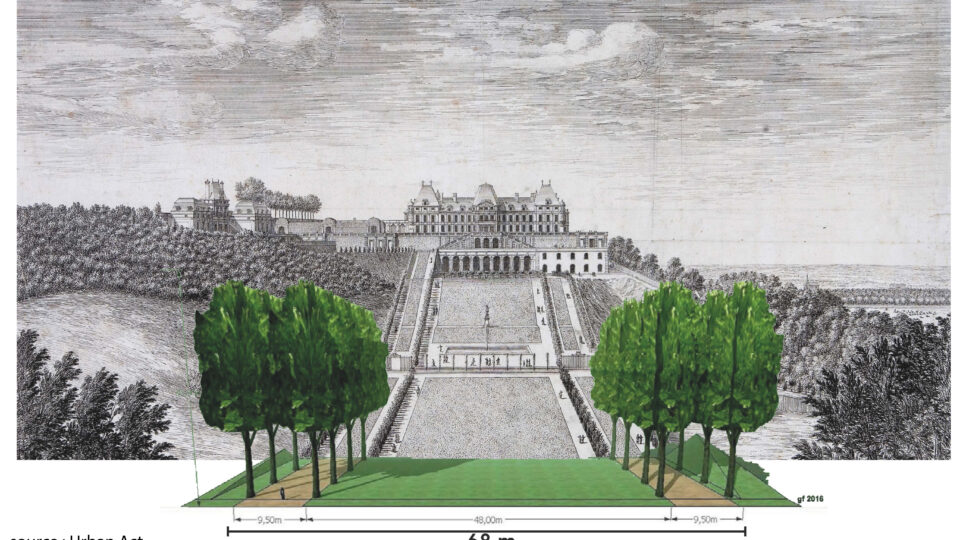

The historic axis, 68 metres wide, consists of a 48-metre-wide lawn, flanked by two 9.5-metre-long avenues, lined on either side by rows of lime trees (Fig.4).

In Le Nôtre's design, architecture and landscape become one when, at the point where the axis meets the pond, one side of the line of lime trees is interrupted to make way for the stone, thus outlining and emphasizing the pond by positioning the green carpet around it and the recessed woodland.

The pool is a regular hexagon, 110 metres on each side: a geometry so perfect, so precisely positioned and aligned on the axis, it's almost sacred.

Le Nôtre designed the hexagon in two stages:

- Firstly, it delimits the water mirror by means of a riprap, underlined by an alignment of thick stones positioned 1 metre above the water level. As shown in these diagrams, the geometry of this riprap frames and limits the water mirror (Fig.5), giving it its distinctive shape and thickness.

- In a second phase, the hexagon of the basin is crowned by an alignment of trees set back 9.5 metres from the perimeter wall, behind the lawn (green carpet) at the center of the historic axis.

EPISODE 6: Cultural heritage, ecological heritage

Reed beds and pond

Over time, the basin was filled with sand and sediment carried by run-off water. So much so, in fact, that at one point in the basin, the outcrop of this mound almost gives you the feeling of being able to walk on it.

Reed beds have developed and play an important role on the water. Here, perhaps more than anywhere else, a Cornelian dilemma arises: how to choose between cultural and ecological heritage? While these reedbeds detract from the hexagonal layout designed by Le Nôtre, they represent an interesting environment for avifauna and entomofauna.

In the end, it was decided to keep the reed beds, because they define a different landscape from Le Nôtre's geometry, one that will be indispensable for years to come. They are proof that vegetation and soil can, in a few decades, completely eradicate built works. These reedbeds are the sign of a landscape in movement, of vegetation that alters and replaces our cultural heritage in the space of a few years. We wanted to highlight this unique landscape atmosphere, as well as the ongoing reconquest of vegetation from the built environment.

An endangered heritage

Trees have also colonized the banks, to the extent that some have grown right up onto the hexagon, right out of the riprap stones.

In its early stages of growth, a young tree poses no danger. However, when it reaches a height of over 15 metres and grows accordingly, the bank is no longer able to resist. All it would take is a stronger wind than usual for the tree to topple over, tearing away part of the historic bank, which would then collapse into the pond (Fig.9).

EPISODE 7: Remarkable trees

Between preserving and strengthening the tree heritage

Each tree has a unique silhouette, determined by the diameter of its trunk, its height and the thickness of its crown. Depending on the quality of their silhouettes, their characteristics and their physical and structural qualities, the most remarkable trees have been preserved and enhanced.

Despite its location in the historic axis, the plane tree's unique appearance, its tall, slender trunk, its dense crown, its presence and its robustness have made it a feature of the landscape and the promenade.

A little further towards the pond, on the bank to the left of the plane tree, a very tall chestnut tree has sprouted, with three trunks growing from the same stump.

A total of 40 trees had to be cut down due to poor condition, disease or stability problems.

In return, we planted more than 1,300 trees on the site:

- 176 trees with a diameter of 25 cm and a minimum height of 4 metres.

- 187 shrubs 6 to 8 cm in diameter and 50 cm to 1.5 m high.

- 978 shrubs 40 to 50 cm tall.

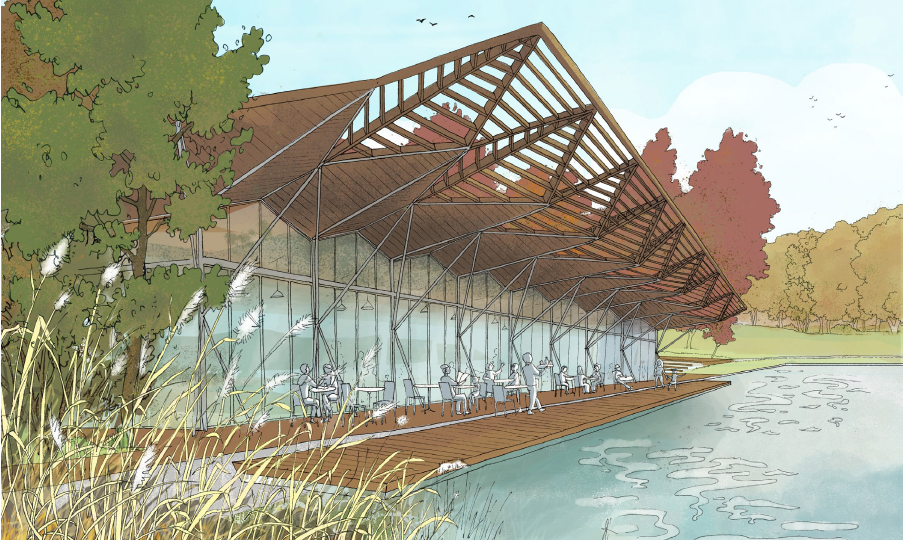

It's because we're committed to rehabilitating a heritage that's at once historical, ecological and cultural that the enhancement of the site is exceptional. It repairs the traces of the past while at the same time making a strong commitment to building for the future, and positioning architecture in solidarity with the landscape, not alongside it! (Fig.10)

Texts : URBAN ACT